Introduction

Among etchers, Fabri is one of the most esteemed artists in the country working in this exacting medium. Technically he is greatly admired for the perfection of his line, the Rembrandtesque richness of his plates and the great beauty of his form.1

—Irwin D. Hoffman, 1942

The Hungarian-born artist Ralph Fabri (1894-1975) studied as an architect before receiving his M.A. from the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Budapest in 1918. He came to America in 1921 and was naturalized six years later, residing permanently in New York. Fabri became an active member of the art community, teaching at the Parsons School of Design in the late forties followed by the Newark School of Fine and Industrial Art and the National Academy School of Fine Arts. Concurrent with the latter position, he served as associate professor of art history at the City College, New York, until 1965. Fabri was an exacting and prolific printmaker, involved in several related organizations such as the Society of American Graphic Artists, the California Society of Etchers and printmakers groups in Boston and Washington. This exhibition was made possible by a recent donation of 80 of his prints, for which the university and the library wishes to acknowledge the generosity of Ms. Phyllis Newbeck.

The Exhibition

Indicative of Fabri’s interest in literature, music, history and religion, the prints in this exhibition are arranged in four thematic groups according to their title: Literary Allusion, Visions of the Ideal, Music and Reverie, and Biblical. Some titles, such as Paradise Lost (categorized as Literary) and Saint Ildefonso’s Vision (Visions of the Ideal) are obviously applicable to more than one thematic category. Such cases were decided largely by visual aesthetics for the purposes of hanging the exhibition.

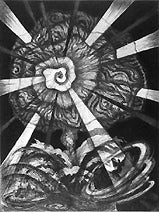

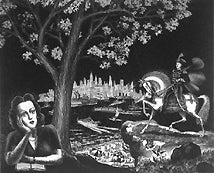

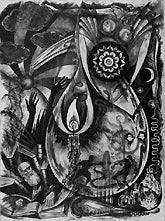

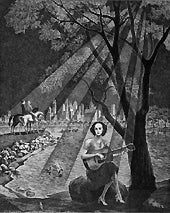

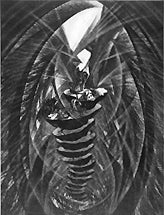

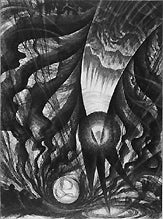

Fabri’s imagery does not always reflect what his descriptive titles suggest. For instance, Midsummernight’s Dream is an illogical fusion of lyrical shapes and forms interwoven with descriptive elements including a pair of horses, a Dali-esque eye and some distant buildings. The overall effect, however, is visually harmonious, evoking the realm of dreams and fantasy. Similarly, the cosmic or divine order is implied in Saint Ildefonso’s Vision, which does not represent the Virgin Mary presenting the saint with a sacred chasuble, as depicted by artists such as Rubens and El Greco. After careful scrutiny one finds the tiny silhouette of Saint Ildefonso engulfed in a beam of light emanating from a tumultuous Blakeian vortex.

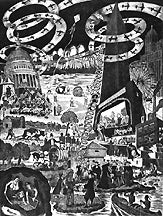

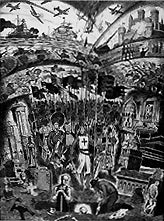

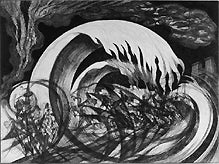

Fabri’s mastery of the etching medium is expressed in contrasting stylistic approaches, one literal, with allegorical overtones, the other abstract, bordering on the surreal. Those prints in the first category, including St. Jerome, Pursuit of Happiness, and Sound and Fury, contain detailed narrative elements divided into compartments or merged together to create the effect of historical anachronism. The more abstract interpretations, including Dream, Raising of Lazarus and Moonlight Sonata, are characterized by swirling lines and evocative, wave-like forms woven together with favored motifs such as equestrian and semi-abstract figures.

Fabri exhibited several music-inspired paintings at the Binet Gallery in 1947 which share the same title as several of his prints (Moonlight Sonata, Scherzo II, Midsummernight’s Dream and A Hero’s Life). It seems likely that he later translated some of these watercolor and tempera works to etching plates. In the exhibition checklist, he explained the different sources of his imagery: “One type was made while listening to music, spontaneously... The other is a group of compositions inspired by music and dance... It is not important to know what music had inspired this or that picture, just as it is not important to know the title of a musical composition before one can enjoy listening to it.”2

Many of Fabri’s prints reveal the psychological impact of the Second World War. Fighter planes resembling menacing birds are a recurrent motif, as in St. Jerome—who peers over his shoulder to witness the destruction of Europe, and Sound and Fury—which presents a composite picture of war throughout the ages.

According to a contemporary critic, “[Fabri] is haunted by features of the war, particularly searchlight beams sweeping the dark skies and picking out innumerable airplanes. ...these plane-filled ribbons of light … are strong and effective patterns….”3 Paradise Lost, printed in sepia and dated 1930, seems to anticipate the horrors of the war with its mass exodus of birds and animals behind Adam and Eve, fleeing from the garden where a tree bearing swastikas has grown.4 When Paradise Lost was exhibited at the Smithsonian Institution in 1942, along with several other prints in the current exhibition, the local press commented on Fabri’s moving interpretations of the effects of war:

The etchings by Ralph Fabri at the National Museum are a revelation of the possibilities of the power of graphic art in commenting on the international situation. Seldom have we seen an artist who has the cosmic point of view and the power to express it in significant form at the same time. Fabri’s etchings are pertinent to the pageant that is marching past today. [They] have a quality of emotion and thought carefully considered and stimulate one’s reaction to the tremendous change that is taking place.

—Washington Post, December 6, 1942

Another writer observed:

Mr. Fabri’s subjects are individual, and reveal a sensitive mind preoccupied with the war in its many complicated relationships and its place in history…. All the details of his plates are represented naturalistically and his allegories give an effect of historical pageantry.

—Washington Star, December 13, 1942

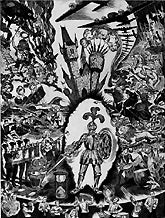

Such pageantry is one of the primary features of To Be or Not to Be, which was awarded the John Taylor Arms Prize from the Society of American Etchers in 1943. Fabri borrowed the famous line from Hamlet’s soliloquy (III:i) to characterize the eternal struggle for domination and survival depicted in his print. In the foreground, he represents himself as one of the grave diggers, assisted by a friend who later became a wartime pilot in the Pacific theater. Beyond their grave are legions of fighting armies led by famous military warriors, framed by the tombs of historic world leaders.

In an effort to support the U.S. involvement in the war, a number of artists not employed by the federally funded WPA (Works Progress Administration) joined together in 1942 to form Artists for Victory, Inc. This non-profit group, comprised of over 10,000 artists nation-wide, adopted the philosophy of President Roosevelt’s address before Congress of January 6, 1941, in which he asserted the necessity of U.S. involvement in the war. His historic “Four Freedoms” speech, which called for freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want and freedom from fear, inspired a number of artists, including Ralph Fabri and Norman Rockwell.5 Artists for Victory worked to connect government, industry and businesses with artists to create visual material on behalf of the war effort. The designation of four days in September 1943, as the official observance of Four Freedoms Days, spurred Artists for Victory to form their own Four Freedoms Campaign to improve interaction between artists and local communities in an overall effort to help win the war. This ambitious program included a national printmaking competition entitled “America in the War,” in which the 100 winning entries were exhibited simultaneously in 26 museums across the country.6 Included in the exhibition was Ralph Fabri’s etching, the Four Freedoms, illustrating Roosevelt’s ideals for world peace.7 Fabri was an active member of Artists for Victory and served as head of its Graphic Arts Committee in 1945.8

Ralph Fabri’s distinguished career included membership in a number of artists’ organizations such as the National Academy of Design, the Royal Society of Arts, London, and Audubon Artists, among others. Beginning with his first solo show in 1938 he exhibited frequently throughout Europe and America and was awarded numerous prizes. In addition to teaching, he contributed regularly to Today’s Art, of which he was associate editor, and published popular how-to volumes on mastering techniques such as oil painting, color application, paper sculpture, drawing and composition. Yet despite the prophetic words of one of his admirers, that “Fabri’s plates will have a permanent place in American Art and will be cherished by a grateful posterity,”9 the artist is relatively unknown today. We hope this exhibition at Georgetown University will help revive interest in and appreciation of his work.

LuLen Walker

Art Collection Coordinator

Notes

- Dedication in the brochure for Fabri’s exhibition at the Smithsonian Institution, December 1-31, 1942 (Division of Graphic Arts), on file in the Smithsonian American Art Museum Library, Washington, D.C.

- Brochure for the Binet Gallery exhibition, New York, on file in the Smithsonian American Art Museum Library, Washington, D.C.

- Review of Fabri’s solo exhibition at the Smithsonian’s Natural History Building, published in the Washington Star, December 13, 1942.

- This foreshadowing of the war in his early prints was noted by Howard Devree in the New York Times (Section 2, p. 8x), Sunday February 25, 1945. The review accompanied Fabri’s exhibition at the Modern Art Studio (George Binet Gallery).

- Rockwell created the popular series of Four Freedoms paintings which were reproduced in the Saturday Evening Post and became incorporated into promotional imagery for a massive U.S. War Bond campaign.

- Each artist was required to provide 25 impressions in addition to the one submitted for the competition. This probably accounts for the large edition size of Fabri’s Four Freedoms, from which he pulled 100 impressions. He usually limited his editions to 50, 30, or 25 impressions.

- A complete set of the 100 winning prints was donated to the Library of Congress, which mounted an exhibition of them in 1983 accompanied by the catalog Artists for Victory, by Ellen G. Landau (Washington, D.C., 1983). Her illuminating introduction, particularly pages 2-3, provided the source material for the paragraph above.

- Ibid., p. 36.

- Irwin D. Hoffman (1901-1989), portrait painter, lithographer and etcher who (like Fabri) received the John Taylor Arms prize from the Society of American Etchers and the Pennell Purchase Prize (Library of Congress). Hoffman included a praiseworthy dedication in the brochure for Fabri’s 1942 solo exhibition (cf. note #1).

To Be or Not to Be

1942

Etching

30.3 x 22.8 cm

Winner of the 1943 John Taylor Arms prize, Society of American Etchers