March 21, 2022

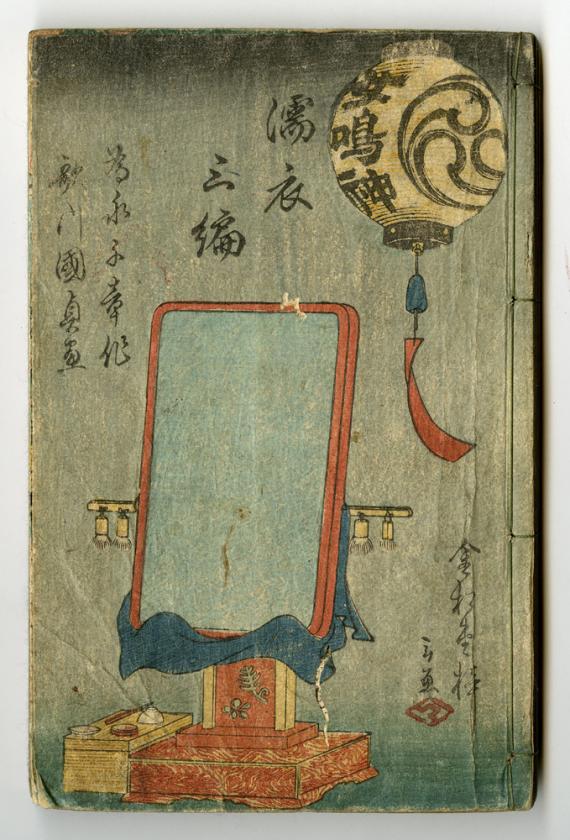

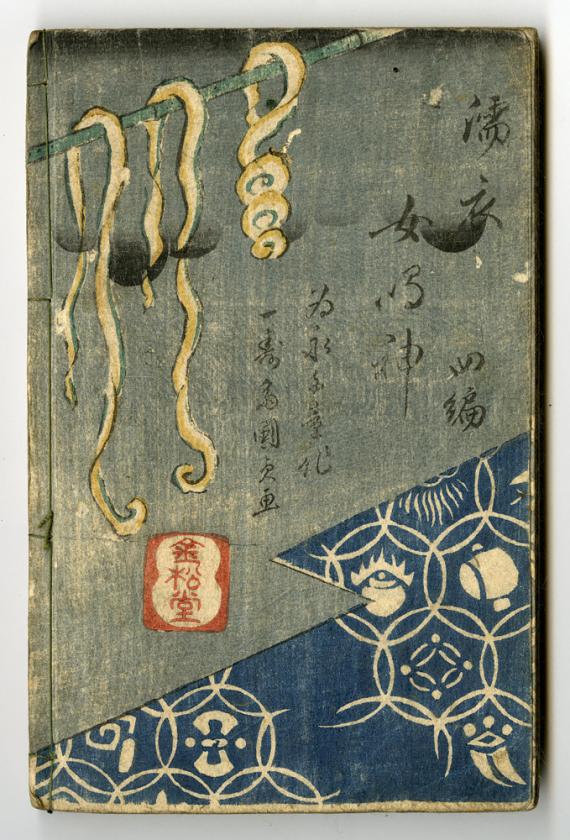

During my time as a University Art Collection Student Assistant, I have had the privilege of cataloging several pieces of incredible art from donors such as Ingrid Rose. In one of these donations, I encountered what may be my favorite thing I had seen yet: two small, Japanese woodblock print books from the 19th century called kusazōshi. Both were by the same artist, Utagawa Kunisada (1786 – 1865), a Japanese ukiyo-e print artist who found commercial success in publishing kusazōshi. Alongside these books were two letters from a writer named Chuck, written and sent to his father in 1964.

Although we do not have much information on who Chuck was (we do not even have his last name), the contents of the letters suggest that he was a newlywed living in Tokyo, Japan with his wife Yoko. At the time of the first letter, he and his wife were expecting a baby. These letters seem to be two of several sent to keep in touch with his father, who likely lived halfway across the world in the United States.

The two books were sent separately; the letter that came with the first book, Dōchū sugoroku (道中䨇六) (1821), was likely written in 1964, while the letter that came with the second book, Nuregoromo Onna Narikami (1854), was probably sent some time after the first. Both letters provide a detailed description of the printmaking technique of the books, some background information about Utagawa Kunisada, as well as Chuck’s own opinion on the works.

As I was skimming through the two letters, I happened upon one line that caught my attention:

“These two books are worthless as works of art, but historically speaking they can be quite interesting.”

I was shocked. While I did agree that these books were fascinating pieces of history, I also felt that it was quite extreme to discount them as artistically worthless. This line is what inspired this blog post; I wanted to examine both the books and the letters more closely to better understand Chuck’s perspective on these books, as well as how it might differ from the way we look at them today.

Getting to read through the letters while looking at the same kusazōshi that the letters were referring to was an insightful experience. It was like a time capsule within a time capsule; the letters capture one moment in time when these books were old, but not quite as old, and perhaps not as valuable as they were now.

I think it is truly incredible how art and writing can connect us throughout time. I can read someone else’s insights from over 50 years ago about a work of art created 200 years ago, all while holding both pieces in my hands. These physical relics preserve moments and ideas that may have gotten lost otherwise. While we cannot talk to Chuck today, we can still get a glimpse into what he was thinking when he sent these “worthless” books to his father over fifty years ago. It does leave me wondering if he would still think they were so worthless today. Below, I have transcribed the letters and hyperlinked the images of the kusazōshi pages they refer to in an attempt to replicate the experience of looking at both pieces simultaneously. I hope you enjoy seeing these pages from history.

–Elli Ahn (SFS ’25)

We wish to gratefully acknowledge donor Ingrid Rose for this gift in memory of Milton M. Rose

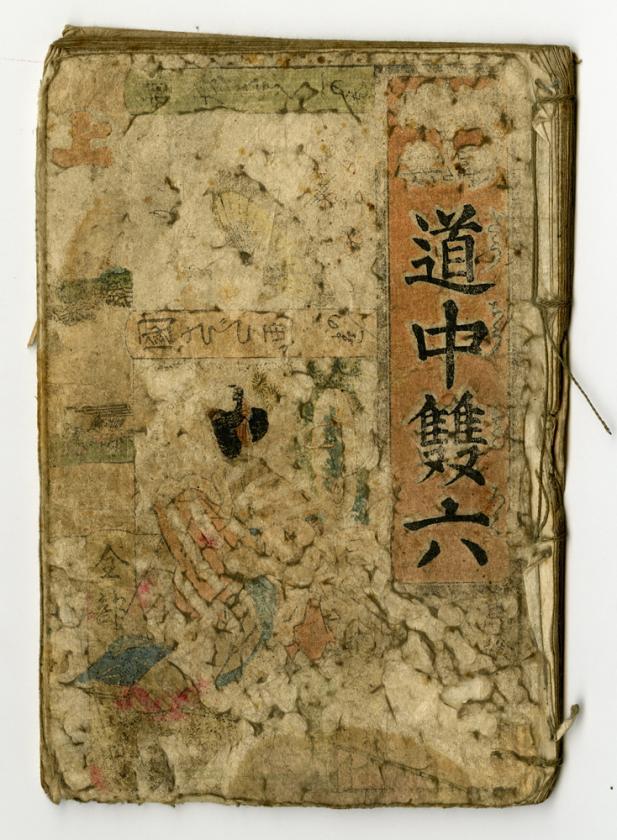

Utagawa Kunisada, "Dochu sugoroku”

engraved and printed by Yanagitei Tanehiko in 1821, 7” x 4 ½”

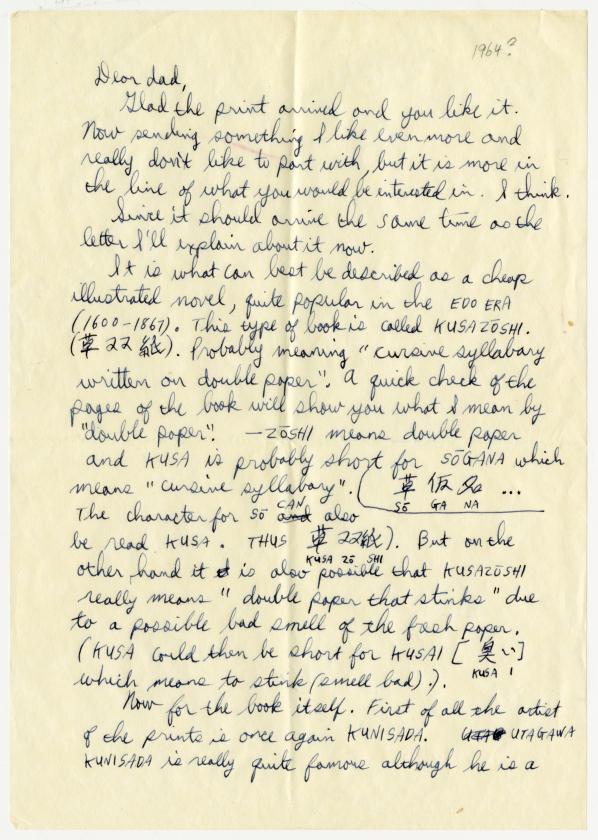

Letter [undated but likely written 1964]:

Dear dad,

Glad the print arrived and you like it. Now sending something I like even more and really don’t like to part with, but it is more in the line of what you would be interested in. I think.

Since it should arrive the same time as the letter I’ll explain about it now.

It is what can best be described as a cheap illustrated novel, quite popular in the EDO ERA (1600-1867). This type of book is called KUSAZŌSHI. (草双紙). Probably meaning “cursive syllabary written on double paper.” A quick check of the pages of the book will show you what I mean by “double paper.” ‒ZŌSHI means double paper and KUSA is probably short for SŌGANA which means “cursive syllabary.” (草仮名 … SŌ GA NA

The character for SŌ can also be read KUSA. Thus 草双紙 KUSA ZŌ SHI). But on the other hand it is also possible that KUSAZŌSHI really means “double paper that stinks” due to a possible bad smell of the fresh paper. (KUSA could then be short for KUSAI [臭い KUSA I] which means to stink (smell bad)).

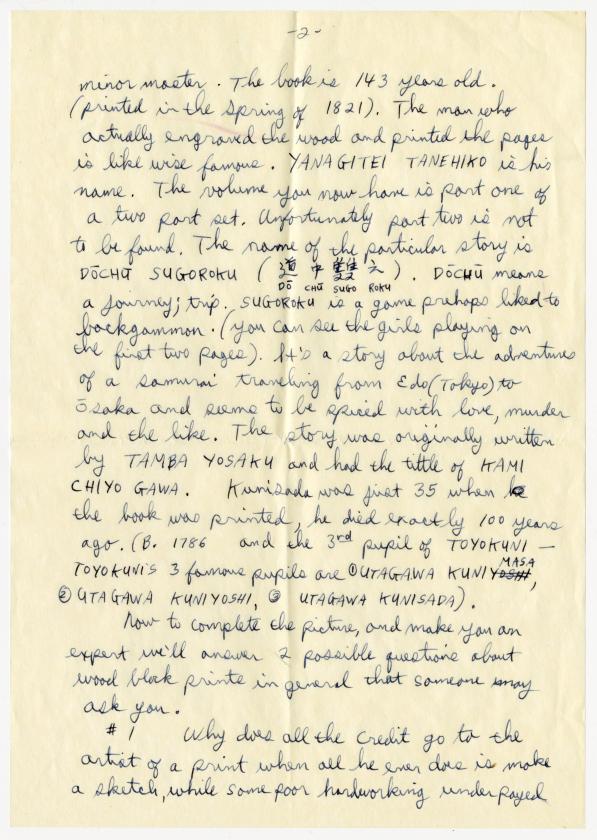

Now for the book itself. First of all the artist of the prints is once again KUNISADA. UTAGAWA KUNISADA is really quite famous although he is a minor master. The book is 143 years old. (printed in the Spring of 1821). The man who actually engraved the wood and printed the pages is likewise famous. YANAGITEI TANEHIKO is his name. The volume you now have part one of a two part set. Unfortunately part two is not to be found. The name of the particular story is DŌCHŪ SUGOROKU (道中䨇六 DŌ CHŪ SUGO ROKU). DŌCHŪ means a journey; trip. SUGOROKU is a game perhaps liked to backgammon. (You can see the girls playing on the first two pages). It’s a story about the adventures of a samurai traveling from Edo (Tokyo) to Ōsaka and seems to be spiced with love, murder and the like. The story was originally written by TAMBA YOSAKU and had the title of KAMI CHIYO GAWA. Kunisada was just 35 when the book was printed, he died exactly 100 years ago. (B. 1786 and the 3rd pupil of TOYOKUNI — TOYOKUNI’s 3 famous pupils are 1) UTAGAWA KUNIMASA, 2) UTAGAWA KUNIYOSHI, 3) UTAGAWA KUNISADA).

Now to complete the picture, and make you an expert we’ll answer 2 possible questions about woodblock prints in general that someone may ask you.

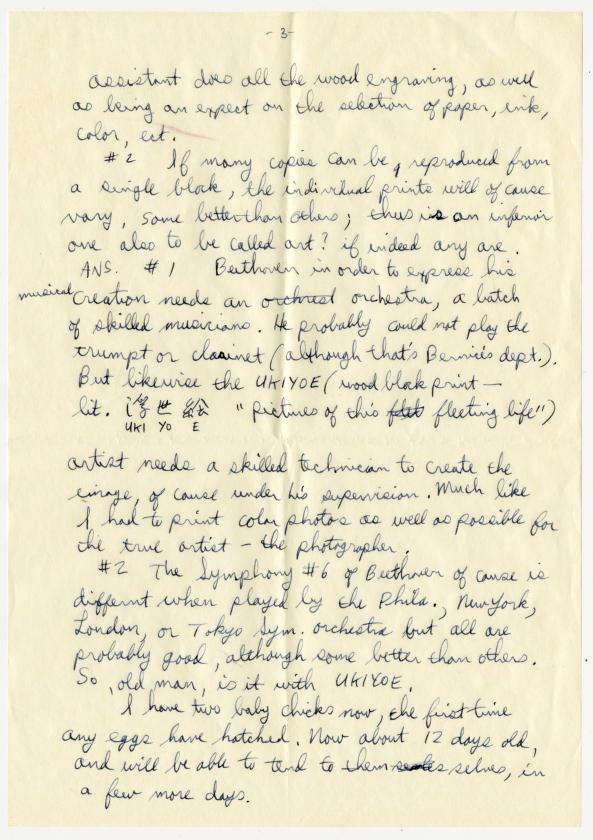

#1 Why does all the credit go to the artist of a print when all he ever does is make a sketch, while some poor hardworking underpayed assistant does all the wood engraving, as well as being an expert on the selection of paper, ink, color, etc.

#2 If many copies can be reproduced from a single block, the individual prints will of course vary, some better than others; thus is an inferior one also to be called art? If indeed any are.

ANS. #1 Beethoven in order to suppress his musical creation needs an orchestra, a batch of skilled musicians. He probably could not play the trumpet or clarinet (although that’s Bernice's dept.). But likewise the UKIYOE (wood block print — lit. 浮世絵 UKI YO E) “Pictures of this fleeting life”) artist needs a skilled technician to create the linage, of course under his supervision. Much like I had to print color photos as well as possible for the true artist — the photographer.

#2 The Symphony #6 of Beethoven of course is different when played by the Phila., New York, London, or Tokyo Sym. orchestra but all are probably good, although some better than others. So, old man, it is with UKIYOE.

I have two baby chicks now, the first time any eggs have hatched. Now about 12 days old, and will be able to tend to themselves, in a few more days.

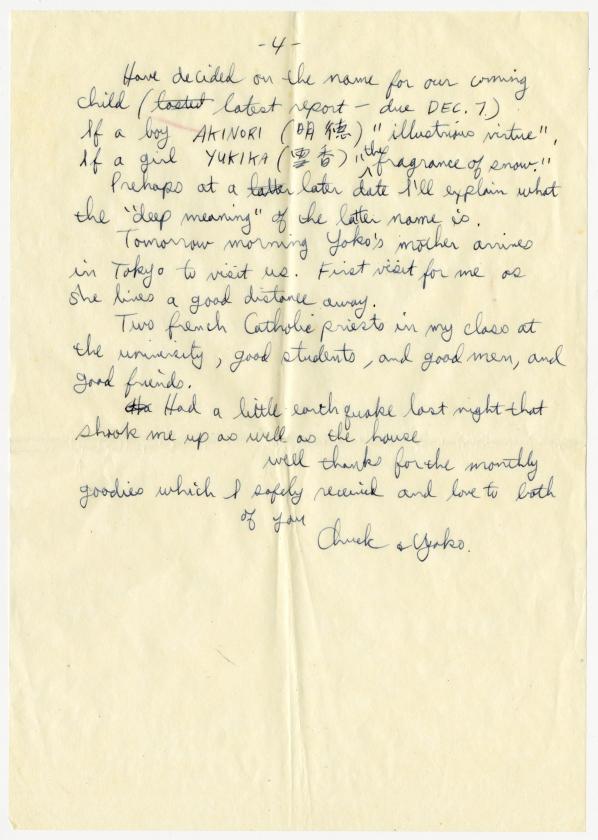

Have decided on the name for our coming child (latest report — due DEC. 7).

If a boy AKINORI (明徳) “illustrious virtue.” If a girl YUKIKA (雪香) “the fragrance of snow.”

Perhaps at a later date I’ll explain what the “deep meaning” of the latter name is.

Tomorrow morning Yoko’s mother arrives in Tokyo to visit us. First visit for me as she lives a good distance away.

Two French Catholic priests in my class at the university, good students, and good men, and good friends.

Had a little earthquake last night that shook me up as well as the house

well thanks for the monthly goodies which I safely received and love to both of you

Chuck & Yoko.

Utagawa Kunisada, "Nuregoromo Onna Narikami"

volumes #3 and 4 bound together, printed 1854 with four full-page color woodblocks, 7” x 4 ½”

Letter [undated but likely written after letter 1]:

Dear dad,

Hope the both of you are in good health. I as usual promptly received my check, for which I express my thanks (i.e. our thanks).

Please thank Bernice again for her kindness, which made Yoko quite happy.

Sending another book (KUSAZŌSHI) by Kunisada. The first one I sent was made when he was 35 years old, the new book was printed when he was 72 years old or in the Spring of 1858. (Kunisada died at 78 years of age — 1864). The name of the new book’s story is, “NUREGOROMO ONNA NARIKAMI” there are ten volumes in all, each volume divided again into two chapters. The one I am sending you is the best of the set, which I own, and is vol #3 and #4 bound together.

Now if you hold the volume in your hands, opening it in the opposite manner of a western book; I’ll tell you a little more about it. First of all the outside jacket was put on at a later date by the publishers. (They might have run as many as 2,000 copies of each volume from the original wood blocks.

Now if we open the outer cover, it merely repeats the fact that what follows is vol # 3 chapter one. Next page is a sort of preface, and has the date — Spring 1854.

Next page is a full page print, done in blue, and black. In places the black has a luster and stands out quite a bit. The black “sumi” ink was mixed with a type of glue to obtain this effect. This was a style quite popular before color prints came to being. MASANOBU (1686–1764) probably was the first artist to apply this principle. This type of picture is called “URUSHI‒E” (lacquer picture). It was applied in the book by Kunisada merely because it’s much cheaper than color.

After a couple of urushi‒e, there are the regular cheap black + white prints. (Before the introduction of color, these first pure black + white woodblock prints were called, “SUMIZURI‒E”, i.e. black printed = picture (a picture printed block).

After these regular prints you will come to a hard cover (the back of it is blue) this is the end of chap. # one, and also an advertisement for the publisher. It was also put in at a later date (around 1863)

Next color print begins chap. #2. Chap. two again is ended by an advertisement (for other books, etc.) also dated 1863.

Next color print begins vol. #4, chap. #1. However the first page is missing therefore it is not dated. However, vol. #4 is probably a work of 1859.

Since it took about a year per volume, furthermore Kunisada signs the work with his pen name, KŌCHŌRŌ KUNISADA, while vol. #3 is signed with his studio name, “UTAGAWA KUNISADA,” and, “TOYOKUNI.” Chap #1 of Vol. #4 ends with an advertisement for the year of 1858, as does chap #2 of vol. #4, therefore there is also a good chance vol #4 was like #3 printed in the same year, i.e. 1858.

Kunisada turned out more prints than any other artist, as a logical result most of his works are of an inferior nature.

These two books are worthless as works of art, but historically speaking they can be quite interesting.

Well, thanks again and love,

Chuck & Yoko.

Letter 1

Letter 2