May 24, 2023

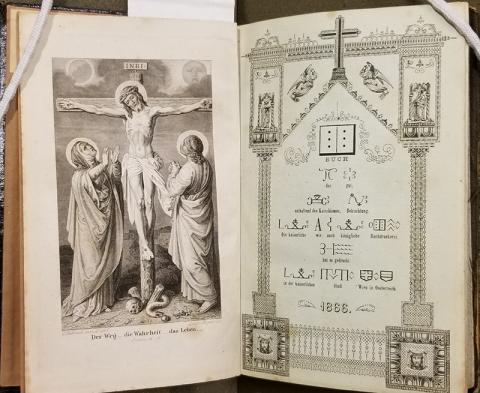

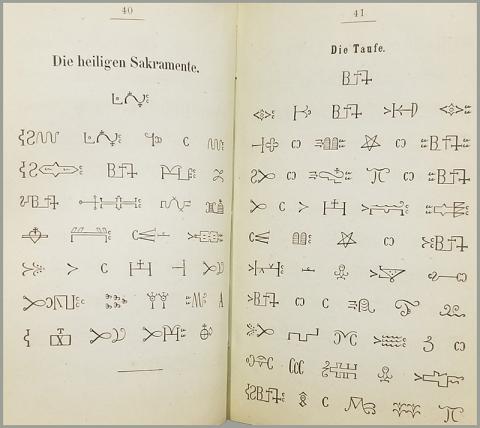

A book—two, in fact—in John Gilmary Shea’s sizable library of Native American language books caught my attention again recently. I say two because the book in question, Buch das gut, enthaltend den Katechismus, Betrachtung, Gesang (The Good Book, containing the catechism, meditations, and hymns), by an obscure 19th-century Trappist missionary from Luxembourg named Christian Kauder, was published in Vienna in two versions in 1866.

The first contained only the “catechism”; the latter contained all three parts. They are a fairly homely affair from the outside, with wrap-around bindings and ties in a rough cloth soaked in dark lacquer as protection from the elements and bookworms. The books are striking not only for their scarcity, but also for the beautiful and fascinating glyphs printed on pale green paper, which fill them almost entirely.

Kauder, who seems to have been a diligent and humble person, made great efforts to get permission and money to create and publish Buch das Gut, including funds for cutting a type font of many hundreds of individual glyphs, at great expense. Much of the first and only print run was lost at sea, on its way to the fishing and lumbering settlement of Tracadie in the Canadian province of New Brunswick on the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

The history of the glyphs used in Buch das Gut is engrossing. They were created during the period after European settlement began along the North Atlantic coast, through the interaction between the Mi’kmaq people (“Micmac” in our 19th-century sources) and the succession of missionaries who came to them from the 17th to 19th centuries. The Mi’kmaq still reside throughout the region of Canada’s Atlantic provinces, the Gaspé Peninsula of Quebec (or Gaspesia), and northeastern Maine. They maintain a distinctly Catholic culture. They have cultural and linguistic ties to other Algonquian peoples of the region, such as the Maliseet, Passamaquoddy, and the Abenaki.

Like other Algonquian peoples, the Mi’kmaq used symbols, similar to the petroglyphs found across the North American landscape, to keep records and tallies, play games, and for other quotidian purposes. They wrote or drew them on a variety of materials: thin birch bark “paper” in the case of the Mi’kmaq, according to the French Recollect missionary Chrestien Le Clercq, who in 1677 noted Mi’kmaq children using charcoal and birch bark to help themselves learn a prayer he had taught them. The Mi’kmaq call their symbols “Suckerfish script” after their resemblance to that fish’s tracks in a shallow riverbed.

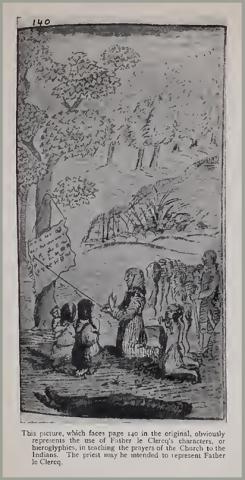

Le Clercq adapted this local practice into a device that could help him to teach the Catholic liturgy to the converted Mi’kmaq, and introduced new symbols as needed. The system was popular with the Mi’kmaq, and its use quickly spread throughout northern New Brunswick and Gaspesia, then through Nova Scotia and into northern Maine. Drawings discovered in a copy of Fr. Le Clercq’s account published in 1691, Nouvelle Relation de la Gaspesie, and reproduced here from the 1910 translation, The New Relation of Gaspesia, depict Mi’kmaq people of the Miramichi band, and include an image of a priest, possibly Le Clercq, using the script to instruct children. Other missionaries to the Mi’kmaq and neighboring peoples noticed this success and made use of the Suckerfish script, including the noted 18th-century Catholic missionary Pierre Maillard, who continued to develop the system and regularize its use. It was finally put into print through the efforts of Fr. Kauder a century later.

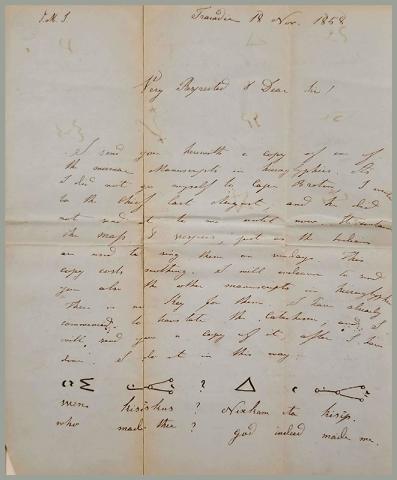

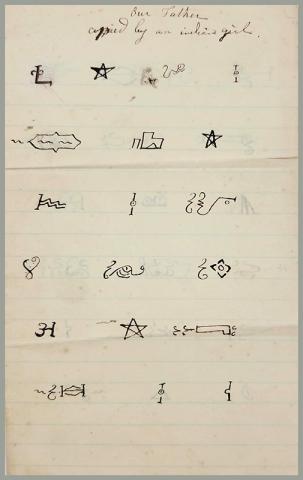

We are lucky that Fr. Kauder’s efforts are documented in the Shea Papers. In one of several folders labeled only “Micmac, is an 1858 letter from Kauder to Shea, just two years after Kauder arrived at the mission in Tracadie. It includes manuscripts in “hieroglyphics” written by a chief in Cape Breton, who wrote the mass and vespers in a pocket ledger as they were used in services at the time. Other “Suckerfish” manuscripts suggest additional letters from Kauder; one of these shows the Our Father “copied by an indian girl”. Kauder gives Shea a brief history of the script, and gives examples as well, with transliteration and English translation in line. He explains that, as there is “no Key for them”, he would provide the same treatment for all the Mi’kmaq writing, if only it were possible to have it printed that way—an endeavor he feared would be too expensive (correctly, it seems).

The Mi’kmaq continued to use the Suckerfish script in their liturgical and devotional practice into the mid-20th century, and have sought to recover their use more recently. Research into the “Mi’kmaq hieroglyphs” since 1990 has sought to determine whether they constitute a complete writing system able to communicate new compositions, or a memory aid that assists the reader in recalling an already familiar expression. The 1995 book, Mi’kmaq Hieroglyphic Prayers: Readings in North America’s First Indigenous Script, by David Schmidt and Murdena Marshall, describes the history and contemporary use of the hieroglyphs in liturgy and asserts their functionality as a full writing system. Research continues today.

If the Suckerfish script proves to be a functional writing system, it would supplant the Cherokee syllabary, famously invented by Sequoyah in the early 19th century, as the earliest indigenous writing of the Americas north of Mexico by nearly a century and a half. In spite of this, the “Mi’kmaq hieroglyphs” remain widely unknown outside of those who live and work in their cultural, linguistic and scholarly context.

--Ted Jackson, Manuscripts Archivist, Booth Family Center for Special Collections